Bob Dylan 49 years listening . . .

49 years listening . . .

Someone somewhere has ventured to call Bob Dylan the best

musician ever.

The site is

everybobdylansong.blogspot.com, and the subtitle for the site is

SPORADIC MUSINGS ON THE GREATEST MUSICIAN EVER. YES, EVER. I like

that. It emboldens me to take up the question, Could there ever

be a “greatest musician,” getting help from Kierkegaard on that.

And I could consider how the greatest musician ever could be doing so

poorly in concerts, of late, on his unofficial “never ending tour,”

which even his die-hard fans think should perhaps end about now.

And there is the problem of his last album, so far, Tempest, which has

its strengths but would not earn him that Best Musician title.

These last questions will appear below in the last two essays below.

Almost two centuries ago the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard, the best

writer in philosophy (some will allow), attended a performance of

Mozart’s Don Juan. Don Giovanni it would have been in

German. Then he went home and listened to it a dozen times

on his CD player . . . didn’t he wish! I picture him in his large open

room with tables all around its perimeter, his little library of future

books abrew at all those tables, and then he came home from the concert

and put it in writing why this was the greatest work of art in world

history. In essence, he said that since music and drama were two

of the greatest art forms, their combination in opera would have to be

the greatest art form. And since Mozart was the greatest

composer, and this his best opera, well, then this is the greatest work

of art.

You can read 42 pages on this topic here (http://www3.dbu.edu/naugle/pdf/kierkegaard_dongiovanni.pdf)

. . . which is wonderful, since 42 is the best of all

numbers. More on that elsewhere. Bear in mind only that not

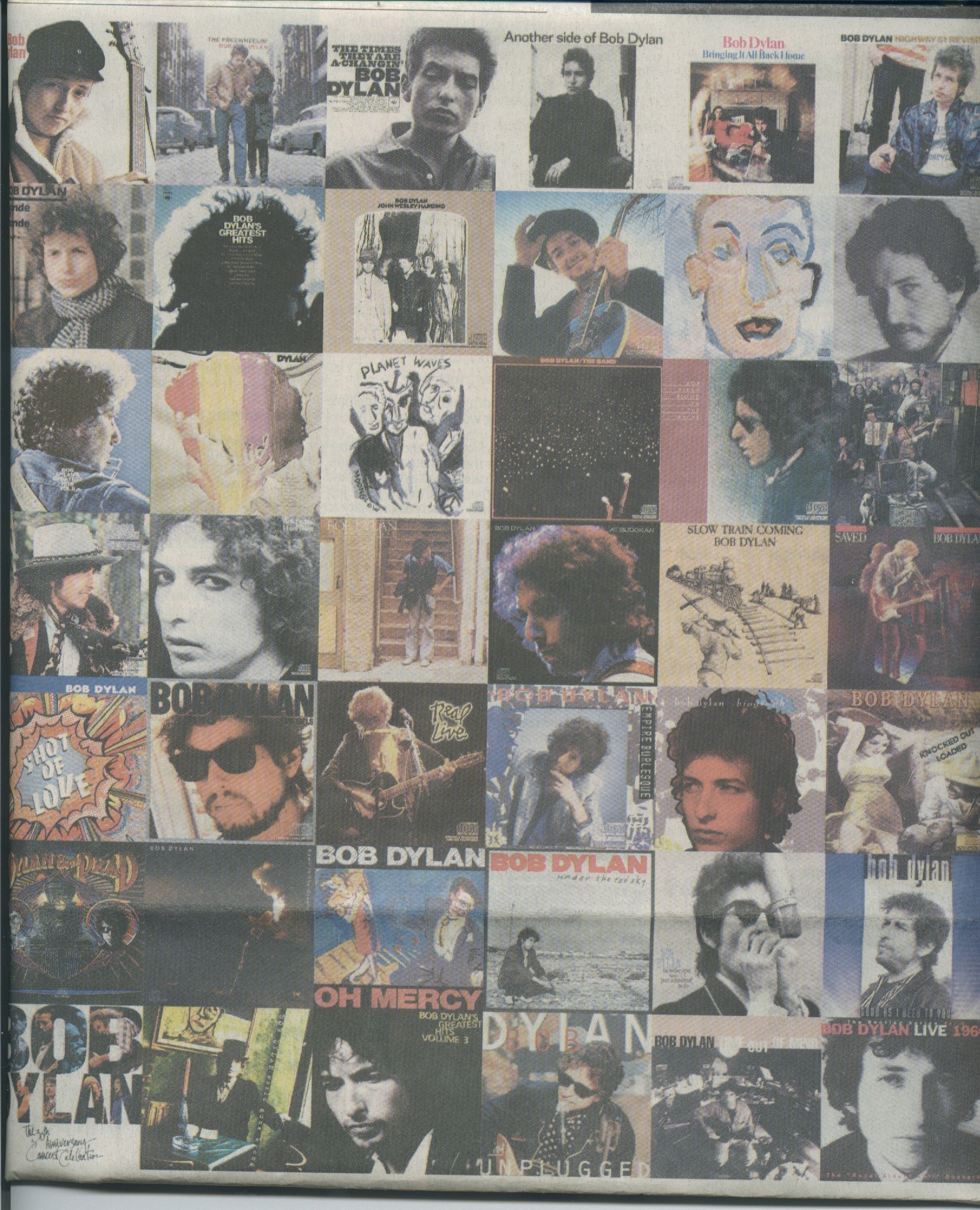

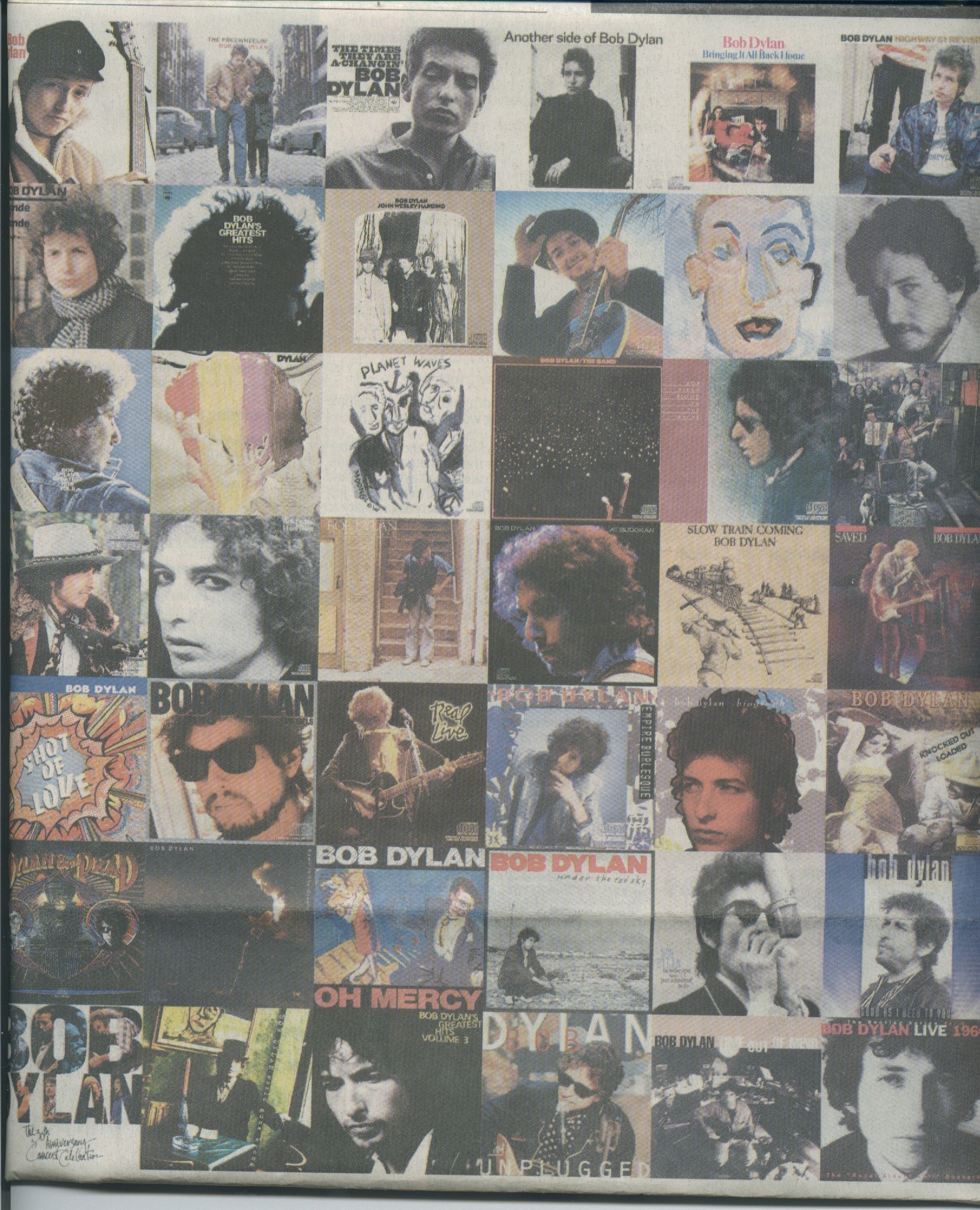

long ago there was 6 by 7 matrix that was all Dylan’s albums. And

Kierkegaard died at 42, as did Elvis Presley, Gilda Radner, RFK, and

Ted Bundy. I was 42 when I began grad school and learned this

about Kierkegaard, who left us 30 volumes of his work, so I thought,

where have I been up til now? But I was assured that philosophers

reach their peak at 80. He wrote his dozen books in his last 12

years, so I have some time left—even now, a quarter century gone by—to

figure out if Dylan is the world’s greatest musician.

This entire situation began to evoke deep and profound questions: Is there

anyway possible to integrate human love with a religious conception of reality? Can

spirituality and sensuality in any way be reconciled? Can freedom be achieved only by

a flight from this world, and by a rigorous detachment from the passions of the flesh, the

world, and the self?27

With this kind of problem, best to circle around for a while . . .

DYLAN’S TOP TEN SONGS

(with links gradually appearing to explain)

Gotta Serve Somebody

Mr. Tambourine Man / Like a Rolling Stone

Hurricane

Brownsville Girl

Forever Young

Visions of Johanna

Bob Dylan’s Dream

Idiot Wind

Man of Peace

Essays

You and You: an Open Letter to Bob Dylan 1997

Aestheticism and Faith: the Bob Dylan Case (academic treatment of the problem)

You and You Only: the Open Letter Revisited (not written yet)

Bob Dylan’s Last Song(s) (2010, 2014)

Bob Dylan’s Last Song(s)

(published in 2010 in the New Mexico Breeze, revised 2014)

In May of 1997, Bob Dylan turned 56 and nearly died from an

attack of histoplasmosis. He recovered, and in September he

released the first studio album of new material in nearly a

decade. Had he not recovered, Time Out of Mind, already in the

can in May, would have given us a clearly designated “last song” from

Bob Dylan. It would have been “Highlands,” with the refrain,

borrowed from poet Robert Burns, “My Heart’s in the Highlands.”

This would have been a comfort to those who paid attention to his

Christian conversion 20 years before and rejoiced with him in three

Christian albums, but then wondered, “What Happened?” The book by

that title, by the way, is about Dylan’s sudden turn into Christianity

and suggested hopefully that it might be temporary. But

Christians were glad and have long been asking if he was really born

again and why it seems not to have lasted.

In Slow Train Coming (1979) Dylan ventured into Christianity, and in

Saved (1980) he declared it unequivocally. Shot of Love

(1981) expressed the struggle of the Christian life, but three

albums in three years said Bob Dylan was a Believer. Then

Infidels (1983) threw the Christians a curve, with its hauntingly

beautiful doubts and second thoughts. “I and I” you could take in

a Chinese way, as “change and change”: the man who cannot be pinned

down cannot pin down his experience of the gospel. Or you could

take it as deconstructing Martin Buber’s I and Thou. He

sings, “I and I, in creation where one’s nature neither honors nor

forgives/ I and I, one says to the other no man sees my face and

lives.” His I-and-Thou experience has been changed to I-and-I,

self-and-self, with no real transcendence in the glimpsed joy that has

left him now. He also sings “Don’t Fall Apart on Me

Tonight,” putting his loss of faith in his favorite metaphor of the

failed love affair.

“Trust Yourself,” in Empire Burlesque (1985), is about as

post-Christian as a song could be, and throughout the album Dylan

explains in painful detail the falling away of his Christian

experience. Those who ignored or wished away Dylan’s conversion

won’t understand this album. The opener, “Tight Connection to My

Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love?)” has two titles because the female

chorus assures him of the tight connection, his security in God, but he

has lost the love he was enjoying, and declares that Christianity no

longer works for him. He sings, “You’re the one I’ve been

looking for, you’re the one that’s got the key, but I can’t figure out

whether I’m too good for you, or you’re too good for me.” Did he

fail to live up to Christianity, or did it fail to live up to his

scrutiny? In any case, he said he was all right “‘Til I Fell in

Love with You,” but then, “I ain’t never gonna be the same again,” and

“I can’t unring the bell.”

In Shot of Love, where the doubts began, he sings the raucous and

mysterious “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar,” and one theory

with Dylan is that he still believes, but 20th century American

Christianity is a runaway bride, something he cannot publicly

embrace. But more deeply imbedded in all his work is the elusive

female Muse, the woman with whom he never could work it out, who

appeared in his very first recorded song and never went away, except by

constantly going away. Her many appearances were for him “Girls

like birds, flying away.” She takes on a special depth with his joyous

Christian period and her loss strikes a tragic chord across the rest of

his work.

Dylan grew quiet and largely sang the blues of other artists during the

eighties and nineties. Oh Mercy in 1988 showed the fruit of his

conversion, and even a repentance from his trademark non-involvement,

as in “It Ain’t Me, Babe.” He had reveled in his cocky evasiveness, but

in Oh Mercy he had to ask, “What Good am I?”—if I can’t respond to her

needs? His long complaint about lost love was there, too,

and he asked, “What Was it you Wanted?” He said he was

doing very well, thank you, without her . . . “Most of the Time.”

He even offered a theological explanation with his shadowy “Man with

the Long Black Coat,” Guilt Himself, who stole away his joy.

What burst forth full force in Time out of Mind was that Christianity

had, like the loveliest of women, taken him for a ride and dropped him

off. “You left me standing in the doorway, crying.” There

is no recovery of his Christian proclamation, just his witness that

what he glimpsed was so great it spoiled everything else. For

those who have ears to hear it is plain that God is in these

songs. In “Cold Irons Bound” he says, “It is you and you only

I’ve been singing about.”

Near the end of that possible last song, “Highlands,” Dylan says, “The

party’s over and there’s less and less to say/ I got new eyes/

Everything looks far away.” The heart of “Highlands” is in a

desultory encounter with a waitress who wants him to paint her

picture. He keeps making excuses, she keeps giving him what he

needs, and then he slips away, and the tone of resignation and

emptiness makes us want to scream at him and tell him to Respond!

Despite his repentance in Oh Mercy from insouciant non-involvement, it

has him firmly in his grip. So, if we have to, we can give up on

him, accept his resignation, and take comfort when he says, “Well my

heart’s in the Highlands wherever I roam/ That’s where I’ll be when I

get called home.” His last words could then have been, “I’m already

there in my mind, and that’s good enough for me.”

Of course Dylan did not die in 1997. Four years later, on the

second Tuesday of September in 2001, he released another studio album,

Love and Theft. One could imagine that he went to Columbia

Records that morning and then traveled a few miles across Manhattan to

see some high-powered associate and was dematerialized in the World

Trade Center. That would have made the album historic from the

start. If it were his last, we could say that he retreated into

the world of professional musicianship, kept his messages muted and

low, and said little about Jesus or God. If that had been his

last album, I would have preferred it close with the penultimate song,

“Cry a While.” He sang all those songs for all those years to

make us feel the pain of our unknown sins and the hurts of our

neighbors, but his sensitivity did not sink in, so now he is gone, and

it is our turn to “cry a while.” But the real last song is

“Sugar Baby,” which ends like this:

Your charms have broken many a heart and mine is surely one

You got a way of tearing the world apart. Love, see what you done

Just as sure as we’re living, just as sure as you’re born

Look up, look up—seek your Maker—’fore Gabriel blows his horn

Sugar Baby, get on down the line

You ain’t got no sense, no how

You went years without me

Might as well keep going now

Here is Dylan’s oft-lost Love once again, whatever we call her.

She is Pleasure herself, or Happiness, his “Shelter from the

Storm.” She is Joanna of his visions, “Brownsville Girl,” or the

“Girl from the North Country.” “She Belongs to Me,” he says

ironically, but when you pursue her you end up “looking through her

keyhole down upon your knees.” Or she is the Christian Muse, the

joy of the gospel. Carnal or heavenly, She is everything

beautiful Dylan ever tried to grasp, but she slipped away.

Dylan lived on, I am happy to say, and in 2006 released Modern

Times. A comforting ending would be “I’ll Be with You when the

Deal Goes Down,” But the song that could have been his last

studio release is “Ain’t Talking.” So do you want to know about

Bob’s foray into Messianic belief? He seems inclined not to tell

us.

He is “up the road around the bend,” not talking, just walking, but

with “heart burnin’, still yearnin’.” “Yearnin’” would have been

a good word on which to end his career, although the actual phrase he

might have left us with is, “In the last outback, at the world’s

end.” Ending with “end,” around the bend, way down

under . . . a fitting last meal for his hungry fans.

The discography of late Dylan gets messy, with new and old material and

some of it looking into the abyss with respect to musical

quality. Together Through Life (2009) starts with “Beyond Here

Lies Nothin’,” which is not what we want to hear, and ends with “It’s

All Good,” which I find unconvincing. Some people on BobDylan.com

liked this one, but I sided with the person who wrote, “Give him his

five stars if you must. Me, I prefer to hold Bob's feet a little

closer to the fire. Blessings to you Bob. Glad you had a good time

jammin' with the boys in Malibu. Hope you had a merry little Christmas.

Now, it's magnum opus time.”

Now it is 2014, and in 2012 we got one more studio release,

Tempest. The critics spoke well of it and loved its

“darkness.” It ends with a pretty song honoring John Lennon, so

at this point Dylan’s last word is, “Shine your light, move it on, you

burn so bright, roll on John.”

Elsewhere in the album Dylan drops his disappointed-theist hints:

“Narrow Way” says over and over, “If I can’t work up to you, you’ll

surely have to work down to me someday.” And “Pay in Blood”

says, “I pay in blood, but not my own.” The title song, a

long and disjointed account of the Titanic tragedy, ends with, “The

watchman he lay dreaming/Of all the things that can be/He dreamed the

Titanic was sinking/Into the deep blue sea.” Odd that he shrinks

the whole grim narrative into the dream of the watchmen—then, as that

watchmen, drops the best of human hopes into the deep blue

sea.

If there must be a last song among what we have today, I choose “I’m

Not There,” from the 2008 film by that name. Six people play

Dylan in this fanciful illustration of his evanescent identity. The

song is raised up from long-ago Basement Tapes, and LAWeekly.com calls

it “Bob Dylan’s Most Mysterious Recording.” In the movie the song

starts in a noisy crowd scene, and in the audio it sounds like someone

dropped the stylus onto the vinyl fairly near the edge. You run

with it, trying to get the sense of it, and it never comes together,

but you want it to—like Dylan wanted Life to come together.

People say Dylan can’t sing, but only a few recordings are mushy, and

many are enunciated with astounding power. The lyrics often take

you far afield and have you wondering what he is talking about, but

somehow the title line will reappear and draw it together again.

But “I’m Not There” is unique. It does for me musically

what life seems to have done for Dylan: it draws me with its simple,

compelling melody, and I glimpse again the tortured Muse of his long

travail, his “Christ-forsaken angel” (or “Prize-forsaken,” some

think). But while other songs are puzzling or obscure, this one

is shot through with holes; it is “breaking up” like a cell phone,

fractured. This is hard to describe: it does not break up phonically,

like a mike with a bad connection, nor distort itself like an analog

radio signal. But it tears itself apart syllable by syllable,

like bursts of dyslexia, and yet he speaks clearly, too.

Dylan clearly says “When I’m there, she’s okay, but she’s not

when I’m gone.” He knows his aestheticist detachment kills his

once-glimpsed, only- satisfying Beauty. In the movie during

this song we see Heath Ledger as Dylan with his kids in the car in the

driveway saying goodbye to his tender-faced wife, who is handing him

their completed divorce papers. “I was born to love her, “ he

sings, “But she knows that the kingdom waits so high above her.”

And I’m crying out for a full grasp of this song, like Dylan reached

out for the utter consummation of his aesthetic and spiritual

journey. About the last thing he has said to us, so far, may have

been, “It's all about confusion and I cry for her.” His final

words, if this were the song . . . “I’m gone.”

If that is too negative, and if Tempest leaves us hanging, then we can

let his last work be his Christmas album, and his last recorded song “O

Little Town of Bethlehem.” Or we can wait for his magnum

opus.

Setlist

Denver, Colorado Bellco Theatre November 1, 2014

adapted from http://www.boblinks.com/110114s.html

1. Things Have Changed (Bob center

stage)

FILM - Wonder Boys

2. She Belongs To Me (Bob center stage with harp) Bringing it all Back Home

3. Beyond Here Lies Nothin' (Bob on

piano) Together

Through Life

4. Workingman's Blues #2 (Bob center

stage)

Modern Times

5. Waiting For You (Bob on

piano)

CONCERTS ONLY

6. Duquesne Whistle (Bob on piano)

Tempest

7. Pay In Blood (Bob center stage)

Tempest

8. Tangled Up In Blue (Bob center stage with harp then on piano) Blood On the Tracks

9. Love Sick (Bob center stage)

Time Out of

Mind

(Intermission)

10. High Water (For Charley Patton) (Bob center stage) Love and Theft

11. Simple Twist Of Fate (Bob center stage with harp) Blood on the Tracks

12. Early Roman Kings (Bob on

piano)

Tempest

13. Forgetful Heart (Bob center stage with

harp)

Together Through Life

14. Spirit On The Water (Bob on

piano)

Modern

Times

15. Scarlet Town (Bob center stage)

Tempest

16. Soon After Midnight (Bob on

piano)

Tempest

17. Long And Wasted Years (Bob center

stage)

Tempest

(encore)

18. Blowin' In The Wind (Bob on

piano)

The

Free-Wheeling Bob Dylan

19. Stay With Me

COVER

(song by Jerome Moross and Carolyn Leigh) (Bob on piano)(FILM: “The Cardinal”)

**********

My Ticketmaster Review

Can Dylan sing? Many say no, but that is because they see him

only on TV and in concerts, where he does not usually sing well, not in

recent decades, anyway. If you hear the studio recordings, and if

you give them time—because he is an acquired taste—you learn that the

greatest musician of our times is also a great singer. His own

work he sings like almost no else ever could. But in concert, in

Denver, in 2014, it was a little rough. Band was loud, his mike a

little high, and then he flattens his well-known melodies and adds

useless ups and down at the end of the song. Also, but not so

much in Denver this time, he shouts out phrases you expect him to

sing. This was an appreciative crowd, hoping for the best, and

they cheered when they figured out what song he was singing.

But the concert was 2/3 late Dylan, the last few albums, including two

from Together through Life, which I refuse to call a studio

album. Six were from Tempest, which though serious, is not quite

Dylan caliber. You wonder if his creative mind is tired, like his

voice. His last words in the main set were, “So much for these

long and wasted years.” But it all ended well with a second encore that

was a cover of “Stay with Me,” which Frank Sinatra made the theme song

of a 1965 movie called “The Cardinal.” I don’t know the movie,

but the song is a very definite crying out to God.

So this is what the concert said: this life on Earth is going nowhere

and is one big disappointment after another, so I need to get back to

the God who once made me happy.” To understand that, go back to

Slow Train Coming, Saved, Shot of Love, and then, in the powerful

post-Christian era, Infidels and Empire Burlesque. Add a few

touches from Oh, Mercy, the fact that he sang the blues all through the

nineties, and then, as the grand conclusion of his struggle, the

magnificent Time out of Mind. In that album, look for “Cold

Irons Bound,” where Dylan says, “It’s you, and you only, I’ve been

singing about.”

The rest of his albums only hint that he is still a struggling

Messianic Jew. The two songs on Tempest that show this, “Narrow

Way” and “Pay in Blood,” he chose not to sing.

**********

Jerry L Sherman

Albuquerque

11 NOV 2014

http://richstone.org/aesfaith.htm

49 years listening . . .

49 years listening . . .